掲示板 Forums - Sentences expressing "allow myself to"

Top > 日本語を勉強しましょう / Let's study Japanese! > Anything About Japanese Getting the posts

Top > 日本語を勉強しましょう / Let's study Japanese! > Anything About Japanese

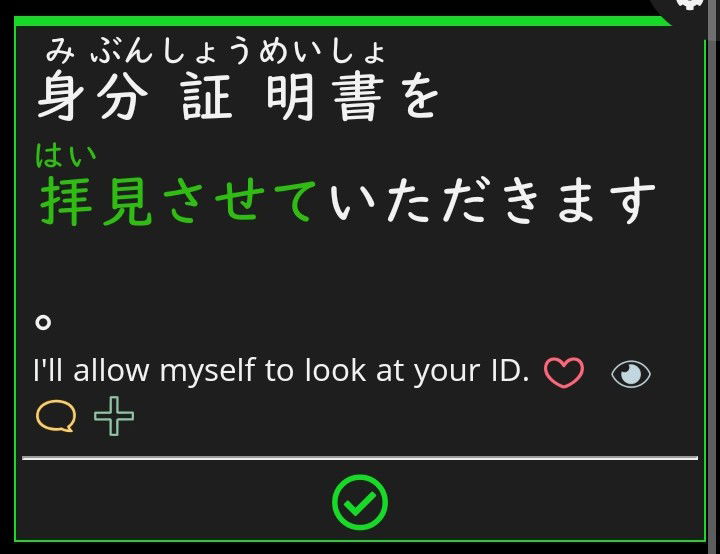

This came up in a vocabulary quiz, but I'm interested in the grammar. I understand the individual words, but I don't understand how the sentence works.

First of all, what is the context? Who might the speaker and the listener be in this sentence? The speaker seems to have some sort of authority, but is using polite speech as well.

Also, I'd like to understand the omitted parts of the sentence.

させる (Causative form)

Subject (causer/permission giver): Speaker

Actor (noun that is supposed to precede the に particle) : Speaker? Listener?

いただく

Subject (receiver): Speaker

Giver: Listener? Speaker?

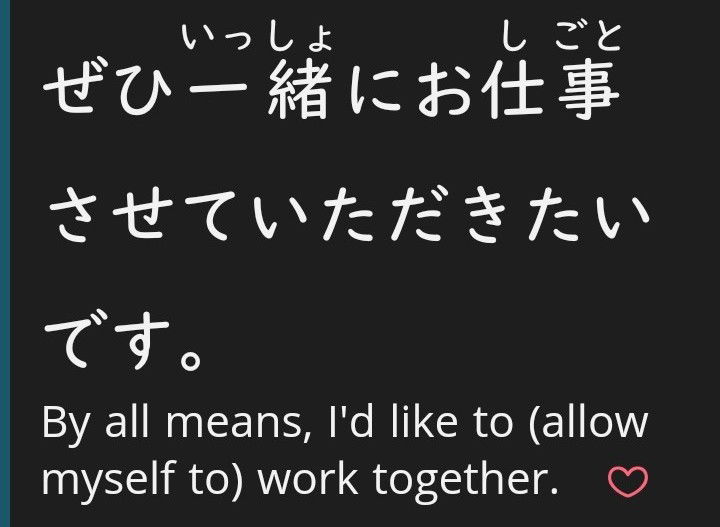

I searched the sentence library using the terms "allow myself" and found the above sentence as well. I have the same questions for this. In addition, why is たい added? Why does the speaker have to want (たい) to do something that they are allowing themselves to do?

させる (Causative form)

Subject (causer/permission giver): Speaker

Actor (noun that is supposed to precede the に particle) : Speaker? Listener?

いただく

Subject (receiver): Speaker

Giver: Listener? Speaker?

If the listener is not instrumental in an "allow myself" situation, am I right that a different type of sentence would be constructed? For example, if I wanted to say, "Just for today, I'll allow myself to eat cake," and it's not the listener's cake, how would I go about it?

させていただきたい is "allow me to do (An action or process) that I want to do". So, essentially the speaker (mostly you): a) want someone's explicit permission or b) want to inform someone politely that you're taking implicit permission.

As for "allow myself to eat cake", I don't think it fits in this grammar pattern, as you're both the cake requester and the cake owner (hopefully). This is you casually informing to your kith or kin that you're relaxing your diet for a day, I think and so, no 'permission' is needed from the listener. If you're talking to yourself, then may be it works kinda, but even then it won't be part of this grammar pattern IMO. A simpler construction like: 今日だけで ケーキを 食べると思う will suffice, no?

It's commonly heard in formal settings, such as airports or official establishments, where staff members interact with customers or the public. When a security officer or staff member uses this phrase, they're essentially saying 'I will humbly receive permission to check/inspect.

The complexity comes from several Japanese linguistic concepts working together:

First there is いただくliterally meaning 'to receive'

Unlike English where receiving requires a physical object, Japanese allows 'receiving' of actions (saseru = indicating making or allowing) and therefor permissions. Think of it as 'being granted the honor to do something' (seemingly without a direct giver). Combined it creates the nuance of 'being allowed to receive permission'.

In practice, it's used when the speaker needs to perform their duty but wants to show maximum respect and politeness. For example:

Security officer: 「お荷物を拝見させていただきます」

The second one I would formulate as: 今日だけは、(あなたの)ケーキを食べさせていただきます(ね)

Maybe this clears it up a bit, if you have follow-up questions let me know.

Short side note: In these examples you do not necessarily receive proper permission as the action being conducted is inevitable. いただく is used to soften it a bit. There is no real permission granted here. Literally: "I receive making it so I can look at your ID" -> "I proceed doing...".

As for "allow myself to eat cake", I don't think it fits in this grammar pattern, as you're both the cake requester and the cake owner (hopefully). This is you casually informing to your kith or kin that you're relaxing your diet for a day, I think and so, no 'permission' is needed from the listener. If you're talking to yourself, then may be it works kinda, but even then it won't be part of this grammar pattern IMO. A simpler construction like: 今日だけで ケーキを 食べると思う will suffice, no?

Yes, that is the sense I get. In English, when we say "allow myself to," there is usually nothing we want from the listener, as in my cake example or, say, "I'll allow myself to spend a little more than I have budgeted."

Both examples in the original post, however, do involve the listener (looking at listener's ID, inserting self (?) into listener's work situation), and from the English perspective feel like atypical/unnatural usages of "allow myself to." That is why I surmised that いただく is for the benefit of the listener.

Thank you! Your translation of the cake sentence makes sense and clarifies my doubt.

Short side note: In these examples you do not necessarily receive proper permission as the action being conducted is inevitable. いただく is used to soften it a bit. There is no real permission granted here. Literally: "I receive making it so I can look at your ID" -> "I proceed doing...".

Thank you for your detailed and clear explanation.

I understand that no real permission is granted. Grammatically, could I say that

させていただく yields the translation "I allow myself to" because the subject of いただくis "I" whereas

させてくださる yields the translation "you allow me to" because the subject of くださる is "you"?

I have questions about the second example: ぜひ一緒にお仕事させていただきたいです。

What might be a plausible scenario motivating this statement? If no real permission is granted, then the speaker seems to have the authority to insert themselves into the work situation of the listener (to collaborate?). So does the speaker outrank the listener? Is ぜひ a hint of genuine enthusiasm, a polite show of enthusiasm, or a threat?

Thank you so much!

The permission or offer was most likely already given. So for example, boss might have said "I've got this special job that I'd like you to work with me on", and so you could respond with this. Even though it was the boss asking you, this still shows a bit of humbleness in your response (acceptance).

Short side note: In these examples you do not necessarily receive proper permission as the action being conducted is inevitable. いただく is used to soften it a bit. There is no real permission granted here. Literally: "I receive making it so I can look at your ID" -> "I proceed doing...".

Thank you for your detailed and clear explanation.

I understand that no real permission is granted. Grammatically, could I say that

させていただく yields the translation "I allow myself to" because the subject of いただくis "I" whereas

させてくださる yields the translation "you allow me to" because the subject of くださる is "you"?

I have questions about the second example: ぜひ一緒にお仕事させていただきたいです。

What might be a plausible scenario motivating this statement? If no real permission is granted, then the speaker seems to have the authority to insert themselves into the work situation of the listener (to collaborate?). So does the speaker outrank the listener? Is ぜひ a hint of genuine enthusiasm, a polite show of enthusiasm, or a threat?

Thank you so much!

I'm glad you understand things a bit better now. Regarding your questions:

Yes, the idea behind させていただく is similar to "I allow myself to" in English.

However, させてくださる on the other hand does not per se mean "you allow me". Let me go into some more Japanese concepts before I answer this question.

In Japanese culture, linguistic politeness is deeply connected to the concept of social hierarchy, where the speaker typically positions themselves lower than the addressee in conversation. Imagine this hierarchy like a mountain:

When speaking to someone , you position yourself at the foot of the mountain, while the person you're addressing is positioned higher up.

This hierarchical concept is reflected in Japanese giving and receiving verbs, which literally incorporate the direction of the action (up or down):

Hierarchical Giving verbs:

Hierarchical Receiving verbs:

Neutral Receiving verbs (no nuance towards hierarchy):

もらう - neutral "receive"

いただく - humble "receive" (no direct giver, abstract reception possible)

Let me put this into context with some examples:

先生が本をくださいました。 The teacher gave me a book. (gave down to me)

友達が本をくれました。 My friend gave me a book. (same thing)

先生に贈り物をさしあげました。 I gave a gift to the professor. (the professor is the other person and since I, the speaker, am on the bottom I give upwards)

妹が母に本をくれました。 My sister gave a book to my mother. (works without direct involvement of yourself. My sister is the subject that is giving down.)

上司からアドバイスをいただきました。 I received advice from my superior. (Using kara to indicate a direction from which the reception is coming from)

友達に本をあげました。

I gave a book to my friend. (I think you get it by now but my friend is above me so I give upwards)

Let's go full circle now and answer your question. The concept of させてくださる means something along the lines of "make possible/allow downwards". If I am the speaker or rather the subject then it can indeed mean "you allow me" as long as the context is providing a sender for the reception that corresponds to "you". Something like 君 or 彼女 etc.

Your second question is quite straight forward. ぜひ一緒にお仕事させていただきたいです。

ぜひ means something like certainly, for sure or no question

using いただきたい actually gives us kind of a "Please allow us working together" kinda vibe, but not how you might expect. It's actually the たい that is interesting here. It shows a strong bodily desire towards something. In other words, you really want to "receive" the "させて -> making possible" of ""仕事". You can only want what you do not have, therefor, something out of your control is preventing you from receiving (the lack of permission or consent from the other person / party). This might be used by a boss talking to some personnel but to me it sounds much more like someone wanting to work together with another person.

I am not a huge fan of modern Japanese "grammar formula" teaching. As these concepts are never truly explained individually but always in conjunction with other unrelated terms. I think many people would be less confused if they'd know what is truly going on.

If you still have questions regarding your original message or new ones let me know.

Thank you so much for sharing the information in such great detail, in order to answer my questions. I have carefully noted your points. I guess the biggest surprise for me was 妹が母に本をくれました。Both the giver and the receiver are presumably in the speaker's in-group. I had not thought about which verb would apply, so thank you for teaching me something new with that sentence, on top of everything else!

Thank you so much for sharing the information in such great detail, in order to answer my questions. I have carefully noted your points. I guess the biggest surprise for me was 妹が母に本をくれました。Both the giver and the receiver are presumably in the speaker's in-group. I had not thought about which verb would apply, so thank you for teaching me something new with that sentence, on top of everything else!

I made a small mistake there. I meant to say subject not speaker, although the speaker is often times the subject the example I gave did not reflect that. I edited that part. With くれる the giver is always the subject, hence, the person above. The sister is giving and the mother, the recipient is below.

I am glad the explanation helped you this much!

I made a small mistake there. I meant to say subject not speaker, although the speaker is often times the subject the example I gave did not reflect that. I edited that part. With くれる the giver is always the subject, hence, the person above. The sister is giving and the mother, the recipient is below.

I am glad the explanation helped you this much!

Thank you for the amendment. I hope you don't mind that I've strayed from the original questions. I have a textbook that seems to say, in short, that あげる、さしあげる、くれる、くださる、もらう and いただく all involve the speaker or someone emotionally close to the speaker, either as a giver or a receiver.

Is 妹が母に本をくれました。intended as an exemplar of "speaker is neither the giver nor the receiver" or "receiver is part of the speaker's in-group"?

Do あげる、さしあげる、くれる、くださる、もらう and/or いただく get used in third-person reporting, like one would find in a news report, or book synopsis, such as "The fan gave his idol flowers."? Or perhaps do the textbook and other sources mean to say that, where the speaker or speaker's in-group is involved, those restrictions apply?

I made a small mistake there. I meant to say subject not speaker, although the speaker is often times the subject the example I gave did not reflect that. I edited that part. With くれる the giver is always the subject, hence, the person above. The sister is giving and the mother, the recipient is below.

I am glad the explanation helped you this much!

Thank you for the amendment. I hope you don't mind that I've strayed from the original questions. I have a textbook that seems to say, in short, that あげる、さしあげる、くれる、くださる、もらう and いただく all involve the speaker or someone emotionally close to the speaker, either as a giver or a receiver.

Is 妹が母に本をくれました。intended as an exemplar of "speaker is neither the giver nor the receiver" or "receiver is part of the speaker's in-group"?

Do あげる、さしあげる、くれる、くださる、もらう and/or いただく get used in third-person reporting, like one would find in a news report, or book synopsis, such as "The fan gave his idol flowers."? Or perhaps do the textbook and other sources mean to say that, where the speaker or speaker's in-group is involved, those restrictions apply?

You brought up some quite important points here. First of all, what your textbook is talking about is probably the hierarchical upwards / downwards structure we've discussed. Let me add onto that. There is one set rule when it comes to this, we, the speaker, are ALWAYS below everybody else. Hence, if we want to give as the speaker we must use あげる or one of its relatives expressing upwards giving. Now, your in-group is also on the bottom with you, they are on your "side". The main difference lies in the perspective/viewpoint being taken, specifically in the use of くれる versus あげる:

本をくれました

However, compare this to personal context:

Think of these scenarios:

Does that make it a bit clearer?